I thought I would do something different and talk about something a little bit nerdy. In 1869 a man named Fredrick Klein discovered a large basalt stela that appears to corroborate with the biblical account of 2 Kings 3. While there may be some interpretations of these two texts that do not allow for complete harmonization, however, you slice it, you have to contend with the fact that the Moabite Stone explicitly references biblical names and places. Consequently, the Moabite Stone serves as an excellent apologetic against those who believe that the Bible should only be used as little as possible in archeology and dismiss any attempt to understand the Bible as a part of history.

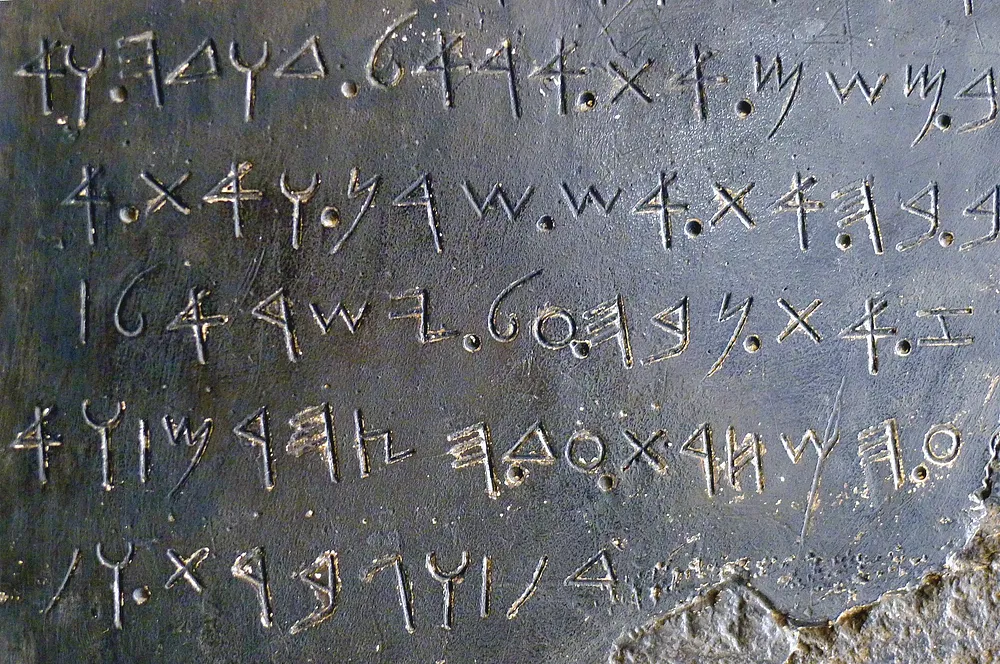

You will also hear the Moabite Stone called the Mesha Stele or the Dibon Inscription. Regrettably, the stone was destroyed due to an ownership dispute sometime in the 1870s. This was owing to a belief that the stone may contain gold. Before its destruction, the large basalt stela stood around four feet tall with a two-foot-wide base. Fortunately, there were some crudely done paper-mâché’ squeezes taken of the stela before it was destroyed. Today, pieces of the original stela can be seen embedded in a re-creation based on those paper-mâché molds.

The Moabite stone was written from the first-person perspective of King Mesha. Like the account in 2 Kings 3, it details Mesha’s kingship over Moab, how he was subjugated to Israel under the leadership of King Omri, and how he led a rebellion against the Omrides. In the stela, Mesha demonstrates a polytheistic perspective and a belief in regional, tribal gods. Specifically, Chemosh, the national deity of the Moabites, to whom he appeals to execute justice against Israel. It potentially differs from the account in 2 Kings 3 in that it seems to imply that Mesha was able to escape the dominion of Israel.

In seeking to understand the chronology, it is helpful to turn to the parallel account in Scripture. 2 Kings 3:8-9 explains that there was a three-nation alliance between King Jehoram of Israel, King Jehoshaphat of Judah, and the King of Edom against the Moabites. After marching northward for seven days through Edom, they began to run out of water. Miraculously, Yahweh provided water for the Hebrew people.

Skeptics will often dismiss the Bible out of hand on the presupposition that such miraculous happenings discredit the Bible. However, this kind of naturalism is a tenuous position that leaves one without a foundation for real knowledge. It is the biblical worldview that gives one a basis to point out how weird it is when things don’t seem to follow the general pattern because it is the biblical worldview that teaches that God consistently upholds creation.

That said, these accounts have distinct biases and do not always agree. To be faithful to Scripture, we do not need to prove that everyone in history always agreed with the biblical perspective. A few places where they seem to differ are on the timing of the war relative to Ahab’s death, and through the presence of a forty-year occupation.” In preparation for this blog, an article that I read by Dr. Joe Sprinkle explained it by pointing out that while the Scriptures date Israel’s war against Judah after Ahab’s death, the Moabite stone states that it occurred during the reign of Omri, and implicitly during Ahab’s life. Thus, the two accounts seem to be contradictory. Another point of distinction can be found in lines 8-9 of the Moabite Stone, which say “Omri had taken possession of the land of Medeba, and dwelt there his days and much of his son’s days, forty years; but Chemosh dwelt in my days.” A forty-year occupation of the land of Medaba under Omri’s rule is difficult to reconcile with the biblical text. In the Bible, Omri’s dynasty lasted 44 years, which was occupied by a 4-year civil war. Thus, many consider these texts to be irreconcilable.

Critics use these (apparent) discrepancies to attempt to undermine the authority of Scripture. This is an awful argument. The Hebrew record has proven itself so reliable that should there be any discrepancy between it and the Moabite inscription, the biblical record should take priority. There is no reason to choose the testimony of the Mesha Stele over the Bible to appease modern naturalist sensibilities. The Moabites appealed to the supernatural just like the Hebrews did.

Furthermore, there are better interpretations of the Moabite inscription that harmonize the two accounts. John Davis attempts to do this in his work The Moabite Stone and the Hebrew Records. As he works to date the stone, he notes three things:

- The Stela is a memorial stela.

- The stela must have been erected after the death of Ahab because the author writes with a knowledge of how long Ahab ruled.

- It was written after the sons of Ahab experienced “utter humiliation” which likely refers to the extermination of his lineage by Jehu in 2 Kings 10.

These three things would place the dating of the Moabite stone sometime during or briefly after Jehu’s reign. Davis then addresses Mesha’s words in the stela that say “Omri had taken possession of the land of Medeba, and dwelt there his days and much of his son’s days, forty years; but Chemosh dwelt in my days.” Davis argues that “son of Omri” can refer to not only Ahab but any descendant of Omri who carries the throne.

While there is some minor disagreement regarding the identity of the son of Omri, there is no ambiguity in that the Moabite stone refers to the Israelites. J. A Emerton writes “To speak to Omri dwelling in the land may in a sense be figurative, but it is clear that the reference is really to the Israelites, as subjects of Omri.”[1] These two texts are not contradictory but complimentary.

There is also the possibility that the Moabite Stone makes a reference to David, although this is, admittedly, somewhat tentative. In lines 12b-13a it says “And I brought back (or took captive) thence the altar-hearth of Davdoh, and dragged it before Chemosh in Qeriyyoth” If this is a reference to David, it would be a unique spelling not found in either the Bible or the Tel Dan inscription. That being said, it is entirely feasible that the ending is a dialectical distinctive relating to how feminine nouns are formed. While there is some uncertainty, the possibility of this being a reference to David remains.

Any set of people who go to war and possess differing worldviews are going to come to different conclusions. So, we should not be surprised when the Mesha Inscription doesn’t 100% agree with the Bible. What should take you off guard, though, is that the Moabite Stone and the Bible, actually agree on a lot of historical realities. Both accounts:

- Affirm there was a Moabite King named Mesha who was subjected to the house of Omri and later rebelled against it.

- Affirm that Chemosh was the Moabite God.

- Affirm that Yahweh was the Israelite God.

- Affirm that Mesha would kill as an act of worship.

- That the Gadites occupied territory north of Arnon

- And, that Mesha was responsible for flocks of sheep.

These parallels should not be overlooked because they ultimately serve as yet another reminder that God is sovereign over all of history. It provides evidence against skeptics who doubt the validity of the Hebrew account. The fact of the matter is the Bible says what it says, and history backs it up pretty clearly. Even assuming that these texts are completely contradictory in no way takes away from its value as a phenomenal witness to the biblical text. Ultimately it doesn’t matter if you think the Mesha Stele can be harmonized with the Bible. The authority of Scripture doesn’t stand or fall on some guy who disagrees with what Jesus has to say – whether he be Moabite or Modernist.